Issue #1

the curious case of mr. brooks

Mr. Brooks, seated in an exam room chair, grabbed an object from his pocket and thrust it in front of me. “Have you seen this thing? It’s amazing!” he said.

It was 2007, the year of the first iPhone release. Mr. Brooks had been one of the first to buy one, and was now proudly holding it aloft for me to see.

I reached into my pocket to grab mine. “Oh, You’ve got one, too!” he shrieked with excitement.

For the next 10 minutes, he gave me a whirlwind, unsolicited tutorial of all of its major features. He wanted to make sure I knew about all the wondrous things this new gadget could do.

Mr. Brooks was there that day to accompany his wife, a patient of mine who sufferred from Parkinson’s Disease. So, after we finished bonding over our shared affection for this revolutionary new piece of technology, I went on with the business at hand.

For the next couple of years, Mr. Brooks and I settled into a routine – at the start of each office visit, I’d ask him about any cool new app discoveries. Invariably there would be multiple, and he would buzz with excitement as he showcased each one of them.

“Check out these filters you can put on your pictures,” he said, while opening up the recently released Instagram app. “Isn’t that fantastic?!”

In between visits, he would often email me internet memes. “Check this one out, Doc,” the subject line would read.

For me, the most remarkable thing about these visits with Mr. Brooks wasn’t the technological breakthrough that was the iPhone, extraordinary as it was.

Rather, the most remarkable thing was that, at the time of our first encounter, Mr. Brooks was 96 years old.

In one of the lessons in the Better Brain Fitness course, I ask participants to think of an inspirational individual who remained mentally sharp and active throughout their lives, and encouraged them to share their selection in the Better Brain Facebook Group. Here are some of those descriptions:

“My mentor is/was Elsa Jennings whom I met at her young age of 92 and was active until her passing at 102. Elsa was always up for a new adventure, making new friends, traveling, daily swims, baking for others, attending lectures/concerts. At 99 she suffered a light stroke but two days later was heading to a cruise with a young friend from Thailand.”

“Then there is my Dental Hero, Joe Warriner who loved Dentistry so much… who was talking about the Art of Dentistry on his death bed in his 80’s. Oh that fire!!”

“My “Grandma-in-law” came into my mind. She made it to the 100, had lived at home until 99 and she kept her sanity until she passed. She did yoga until the age of about 96, did long walks as long as she could and loved reading, travelling and meeting new people”

Over the years seeing patients, I was always on the lookout for long-lived individuals (like Mr. Brooks) who were still vigorous and mentally sharp. Ever since it’s become clear that genes play much less of a role in how we age than once thought, there’s been a collective effort to study “superagers” like Mr. Brooks in order to identify the key lifestyle factors that lead to a long life well lived.

And without a doubt, one of the most consistent traits I’ve discovered in these individuals, which is echoed in some of the comments above, is an eagerness to continue to seek new knowledge and experiences, fueled by an insatiable curosity.

As a general rule, the older we get, the less likely we are to show an interest in new things, including new tools and technologies.

Part of this is instinctual. Relying on established habits and routines is usually the most energy efficient way to live, and we’re wired to conserve energy wherever possible.

But part of it stems from our attitudes.

For some, it may be because it seems like new technologies are trying to solve a problem we don’t have. If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it, right?

For others, it may be due to the misperception that it’s just too complicated for older brains. Many seem to think that new tech is the domain of young folks.

That’s one way to see it.

By the same token, each new piece of technology is a learning opportunity. And the more challenging it is to learn, the better it is for our brain to learn it.

It’s also quite possible that a new piece of technology will add value to our lives. For example, these days there are smartwatches that can detect potentially fatal heart arryhtmias, and websites that help people finally get around to fulfilling their lifelong dream of learning the banjo. 🙂

Mr. Brooks stood out because his attitude towards technology was exceptional. He was the first 90-something-year-old tech geek I’d ever met.

And I don’t think it was because he was oblivious to the above-mentioned drawbacks of technology. Rather, I think it was because his impulse to explore and discover – the impulse we all possess as children – had never really diminished.

That force of his enduring childlike curiosity overwhelmed any objections to the contrary.

And there’s very good, scientifically-based evidence to believe that his insatiable curosity and the fact that he not only had made it to the ripe old age of 96 but looked and acted like someone decades younger were directly linked.

It’s easy to embrace the concept of lifelong learning in principle. It’s much harder to fully realize it in practice. Especially given the forces, both seen and unseen, that push us towards a life of routine and familiarity with each passing day.

But I’ve concluded that the best way to neutralize those forces conspiring to hasten our brain’s demise is to stay curious.

About everything.

BRAIN BOOSTING RESOURCES

In this section, I’ll provide some of my favorite recommended resources for improving brain health and function.

From the Brainjo Library:

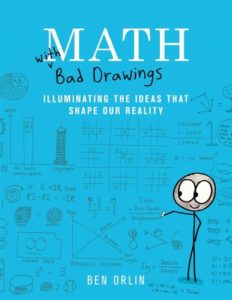

“Math With Bad Drawings“

Now, if a book about math sounds about as appealing as a root canal by a blindfolded dentist, let me tell you two things:

1) This is not your ordinary math text.

If you’ve grown up thinking that math is either dull or you’re not very good at it, that’s not your fault. The version of math most of us get in school has given math a bad rap, and this book is an effort to fix that.

At its essence, math is a set of conceptual tools for the mind, developed and refined by humans over thousands of years.

If you’re already a math fan, then you’ll love this book.

And if you’re not a math fan, this book may well change that.

2) It is hilarious.

On multiple occasions while I was reading this book my wife Jenny would ask me what I was laughing so hard at. “It’s this new math book I’m reading” was not the answer she was expecting.

It’s not just the funniest book about math I’ve ever read (admittedly a low bar), it’s one of the funniest books I’ve ever read, period.

(click here to learn more about how books are selected for inclusion in the Brainjo Library)

Product Recommendation: Wobble Balance Board

Think for a moment about slipping on a patch of ice (which happened to me this week, so it’s still fresh in my mind).

In order to avoid falling, you must first detect that something has knocked you off balance. Those signals come primarily from nerves in your limbs that detect changes in the position of your joints, along with nerves from your inner ear that transmit information about the position of your head.

Those signals are then passed through brain regions including the midbrain and cerebellum.

In response to that perceived balance disruption, your brain then sends output signals via motor nerves to the muscles of your limbs and core to produce a set of coordinated muscle contractions to precisely counteract said disruption.

All of this must take place in a fraction of a second if you’re to avoid an unpleasant encounter with the ground.

In other words, maintaining balance involves significant portions of your nervous system and body.

So, activities that challenge our balance, like the Wobble Balance Board, stimulate widespread adaptations in those systems.

Those adaptations are not only beneficial in their own right, they’re also quite useful. The more “headroom” we can create in our balance system, the less likely we are to suffer a catastrophic injury from the inevitable slips and stumbles that come our way.

Another great thing about the balance board is it’s quite easy to integrate it into your routine, as opposed to having to squeeze some time in your already-full life for “balance board training.” Just put it somewhere that’s easy to access and stand on it for a few minutes while you’re doing something else like watching TV, brushing your teeth, waiting for your coffee to brew, etc.

With practice, your skills will undoubtedly improve, and if you wish you can dial up the level of difficulty in any number of ways (standing on one leg, doing squats or other exercises while on it, etc.).

Noteworthy Neuroscience: Silent Synapses Are Abundant In The Adult Brain

“The adult brain is much more adaptable and plastic than we previously thought.”

You could utter the above phrase each and every year for the past half-century and be right every time.

The more research we do, the more we learn that capacities that we thought were limited to the brains of children also exist in the brains of adults.

The latest example: a study published in November in the journal Nature showed that “silent synapses” are abundant in the adult brain (in adult mice, in this case, but it’s likely this extends to other mammals).

Synapses are central to the brain’s ability to learn and remember, and a “silent synapse” is an immature connection between neurons that remains inactive until it’s recruited to form new memories.

Previously, it was thought that these silent synapses were only present in the very young, exclusively used when the brain is first wiring itself up during early development.

Well, not so much.

Not only do they exist in adult brains, this study revealed that about 30% of synapses in the adult cortex are silent.

As the authors state in the conclusion: “These results challenge the model that functional connectivity is largely fixed in the adult cortex and demonstrate a new mechanism for flexible control of synaptic wiring that expands the learning capabilities of the mature brain.”

The most important takeaway: Virtually every conventional notion people have right now about adult brains is wrong. We’re a long way of knowing the full scope of what’s possible, but it’s safe to say that our potential at all stages of life is far greater than most of us realize.

And I think there’s no project more exciting than understanding that potential and how to release it.