(CLICK HERE to download the “Round Peak Recipe” guide as a PDF book)

Round Peak?

During the Folk Revival in the US in the mid-20th Century, folklorists and other traditional music enthusiasts were on the hunt for undiscovered, “authentic” roots musicians to both study and showcase to the rest of the world.

One place they struck gold was in Round Peak, North Carolina, a small community nestled in the southern Appalachian mountains.

Here, they found a thriving musical tradition, one that was rooted in the traditional fiddle and banjo music of the Appalachian south, yet one that, like the countless regional accents that can be heard within the confines of a single state, had its own distinct character.

Once the music found a wider audience, people liked what they heard. Many musicians, enamored with the rich and deceptively sophisticated sounds of Round Peak, set about to learn it for themselves (many right from the source).

As a result, the music of Round Peak has had a profound influence on the world of southern old-time fiddle and banjo playing. That influence continues to this day.

The names perhaps most commonly associated with Round Peak are Tommy Jarrell, Fred Cockerham, and Kyle Creed. However, there were (and are) many other outstanding musicians from the region.

Regional Styles?

A style of playing, whether it belongs to a single person or multiple people in a particular region, is really just a consistent set of choices that are made when arranging a piece of music.

This workbook, which accompanies the series of videos in Module 14, is a deconstruction of the Round Peak style into its fundamental elements. It is s designed to help you better understand the technical elements that are used to accomplish that sound, emphasizing in particular those technical elements that the Round Peak banjoists used on a consistent basis.

In addition to this manual, I would also highly recommend copious listening to familiarize your ears with the “Round Peak” sound.

Why Study Styles?

One of the common threads amongst master musician is the intense and dedicated study of other master musicians.

By the same token, the hallmark of a master musician is that he or she has cultivated their own unique voice, and has developed the technical expertise to express it. Isn’t this a paradox?

Moreover, as you know, my goal with the Breakthrough Banjo course is not to teach you how to mimic a particular player (myself included). Rather, the goal is to equip you with the skills needed to express yourself on the banjo. Does analyzing (and even recreating) the styles of a specific player or players run counter to this goal?

The resolution of this paradox lies in how we choose to use what we learn through this analysis. The intent here is not to learn to mimic the playing of other players (though doing this on occasion can be a useful learning exercise).

Rather, the intent is to help you acquire as broad a clawhammer banjo sonic “vocabulary” as possible.

Just as having conversations with people of varied experiences and backgrounds expands your spoken vocabulary, listening to players with different styles expands the ranges of sounds you can imagine in the “language” of clawhammer banjo.

Furthermore, studying the techniques those players used to make those sounds gives you with the skills needed to make them for yourself, if and when you desire. In the end, the wider your vocabulary, the better able you are to express the thoughts in your mind, whether you do so through the vehicle of speech or the banjo.

Thus, by studying well developed individual and regional styles, we both expose ourselves to new sounds, and acquire the tools needed to make them ourselves.

You may feel deeply drawn to the music of Round Peak, or you may not. Either way, studying the music will make you a more versatile musician.

This is why the study of styles (both individual and regional) is an integral part of the Breakthrough Banjo course.

Suggested Listening

There’s no better way to familiarize yourself with the Round Peak sound than to spend lots of time listening to it. Here are a few great albums recorded straight from the source musicians:

- The Legacy of Tommy Jarrell, Vols. 1-4

- Down to the Cider Mill

- Stay All Night (Tommy Jarrell, Fred Cockerham, Oscar Jenkins)

- Tommy and Fred: Best Banjo-Fiddle Duets

- Camp Creek Boys: Old-Time String Band

- Benton Flippen: Old Time, New Times

THE RECIPE

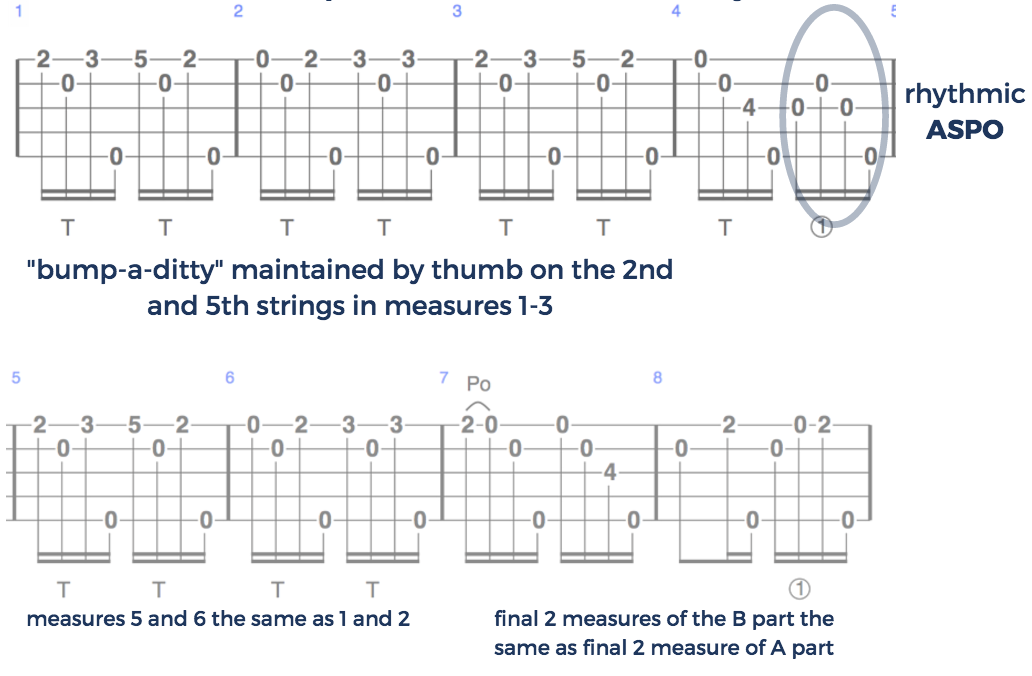

#1: Bump-A-Ditty Backbone

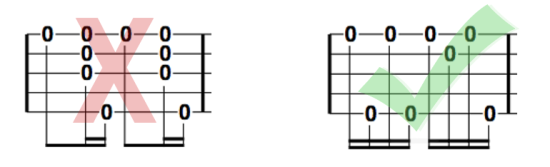

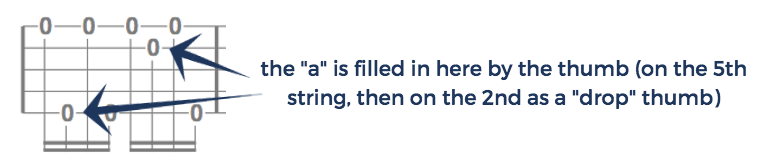

Though it isn’t used exclusively, the “bump-a-ditty” rhythm is heard often in the music of Round Peak. Unlike the “bum ditty” rhythm, where there’s a sonic “pause” after the “bum” stroke, the “bump-a-ditty” rhythm fills this space in, creating a staccato, “machine-gun” like quality to the resulting music.

Achieving this effect means filling the the offbeat after the “bump” strike, generated either by the fretting hand (hammer on or pull off, or the thumb of the picking hand (on the 5th or dropped to an inside string)).

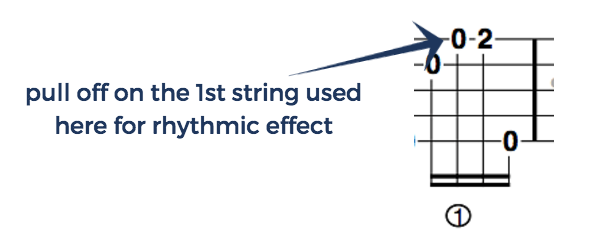

#2: “Rhythmic” ASPOs

As stated above, maintaining the “bump-a-ditty” rhythm means that you must fill in the offbeat after the “bum” strike (the “a” in “bump-a-ditty”)

You can use the thumb to fill that offbeat on a string LOWER pitch than the one you’ve struck on the “bum” strike (on the 5th or an inside string).

To fill that offbeat with a string HIGHER in pitch than the one you’ve struck on the “bum” strike requires a pull-off (an “alternate” string pull off (ASPO), since you’re pulling off of a string other than the one you just struck with your picking hand.

This is unlike the ASPOs that are commonly used in the “melodic” style, as here they’re being employed to sound a melody note that occurs on the offbeat (rather than as a rhythmic effect).

#3: Attack the Neck

One visible way in which the Round Peak banjoists literally left their mark on the world of old-time banjos is in the proliferation of “scooped” banjos over the past few decades.

If you listen to a Round Peak banjo player, you’ll note a distinctive tone, one that might be described as sweeter, more open, and “rounder” than the twangier tones most folks associate with the banjo.

Though there are multiple factors that contribute here, perhaps the largest contribution comes from where they placed their picking hand when striking the strings: typically just above the junction where the banjo neck meets the pot.

Removing the frets and “scooping” out the neck at this spot helps to increase the clearance for the picking hand when playing in this position, a position that many contemporary banjoists have adopted.

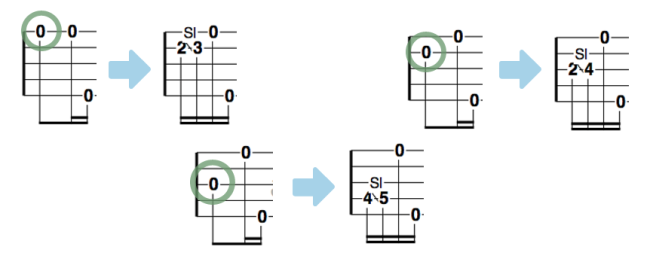

#4: Slide Freely

Slides are used often in Round Peak banjo. One of the easiest ways to add them in is to look for spots where a melody note falls on an open string, and play it instead by sliding up to it on the string below.

Spots for doing this in gDGBD tuning are illustrated above.

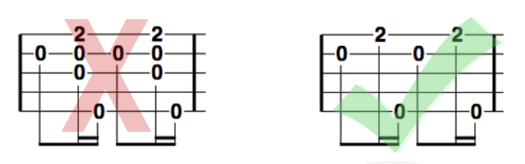

#5: Rare Brush Strokes

Brush strokes (or “strums”) are seldom used on the “dit” stroke when a “bum ditty” pattern is played, replaced instead by a strike on a single string, further enhancing the staccato feel.

#6: A Tuning For Every Key

Round Peak banjoists preferred to use open tunings to play their tunes, which means they would use specific tunings for specific keys (rather than play in all keys out of a single tuning).

aDADE tuning (key of D), aEAC#E (key of A), and gDGBD tuning (key of G) were used most commonly.

Open tunings mean that more open strings can be set vibrating during the playing of a tune in that key. Since plucked open strings tend to ring louder and longer, this gives a fuller sound, and imparts a background sonic “atmosphere” to the tune that’s specific to that tuning. Altogether, this creates a rich sonic experience with just a solo banjo.

Using specific open tunings for each key is now common practice amongst clawhammer banjoists.

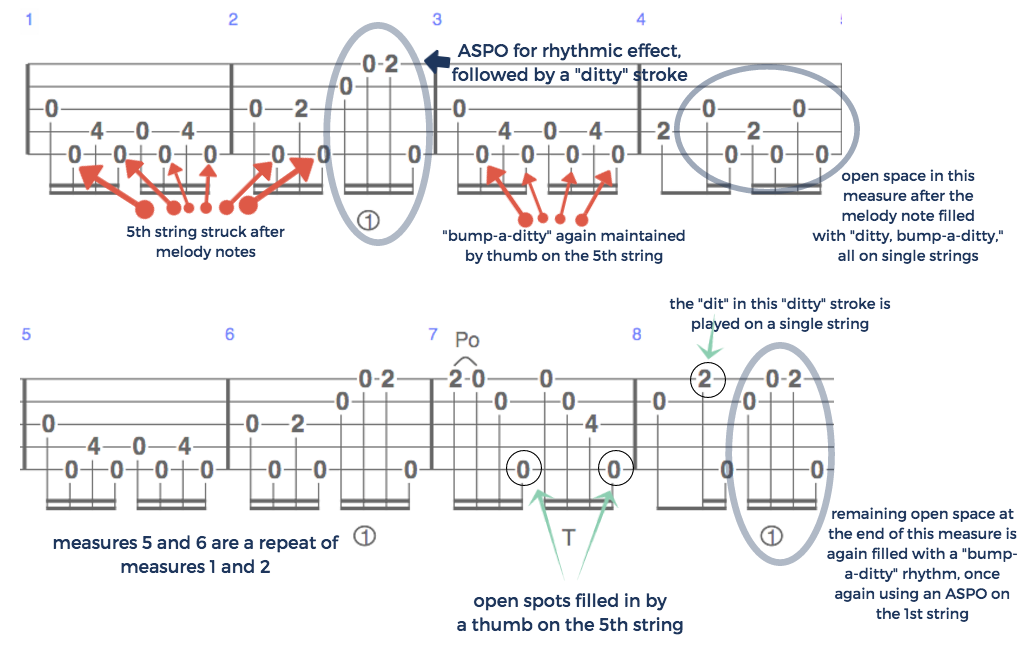

“Round-Peaking” Soldier’s Joy

In my opinion, the best way to learn how to play a arrange in the Round Peak style is to do just that.

To start with, I’m going to take a familiar melody (Soldier’s Joy), strip it down to its essential melody, and then build it back in the Round Peak style.

After that, it’s your turn. I’ve created 9 additional tune arrangements in the Round Peak style, which you’ll also find below.

For each tune, I’ve first tabbed out just the basic melody, free of any clawhammer embellishments. Try your hand at creating your own Round Peak banjo arrangement using this as the starting point, then compare with the version I created (similar to what you did in Part 4 of the “Learn to Play By Ear” module.

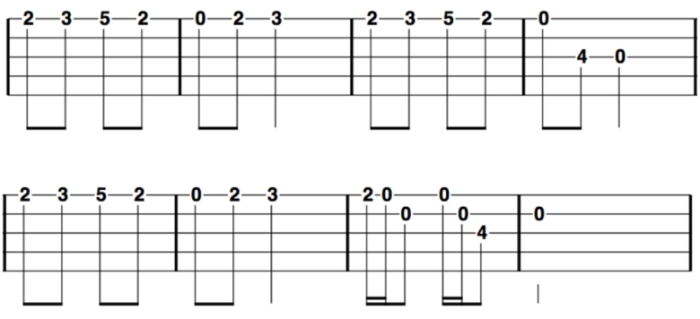

Below is the basic melodic skeleton for the A part of Soldier’s Joy:

Here’s what it sounds like:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/265148797?secret_token=s-O8zdD” params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

Now here’s the A part, arranged Round Peak style:

Here’s what that A part sounds like:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/265148873?secret_token=s-SW5Zw” params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

Below is the basic melodic skeleton for the B part of Soldier’s Joy:

And here’s what the melody sounds like:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/265149208?secret_token=s-xOXJB” params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /] Now here’s the B part, arranged in Round Peak style:

And here’s what that B part sounds like:

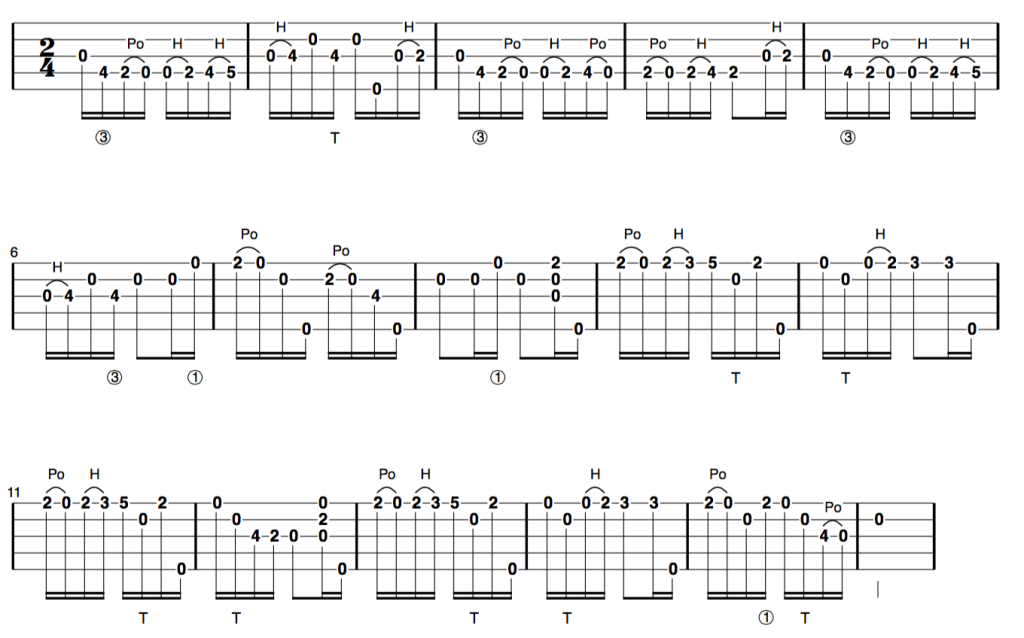

Round Peak vs. Melodic Style

As you can see and hear, Round Peak is a “busier” style of banjo playing, meaning that much of the available “spaces” are filled in with notes.

Melodic style banjo is also a “busy” style, since the primary objective in “melodic” style banjo is to incoporate as many of the melody notes that the fiddle plays as possible (“melodic” style is typically used in reference when discussing adapting fiddle tunes onto the banjo).

With this in mind, you may wonder what the difference between Round Peak and Melodic banjo style is, at least in terms of the labels we use.

The answer is that the central difference is that, in Melodic style, the majority of the notes (with the exception of the 5th string drone note) are melody notes, whereas in Round Peak style, a greater proportion of the notes are used as rhythmic “filler.”

As an illustration of this difference, take a look and listen to this arrangement of Soldier’s Joy in “Melodic” style:

Soldier’s Joy, Melodic Style

And here’s what that sounds like:

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/265150734?secret_token=s-WCHHE” params=”color=ff5500&inverse=false&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

Your Turn!

The best way to internalize these elements for yourself is to try your hand at creating a Round Peak style version of a tune.

I’ve created arrangements of 9 more tunes (plus audio examples) in the Round Peak style, which you’ll find in the following pages.

While you can certainly learn these as is, I’d encourage you to use this opportunity to try your hand at arranging these melodies.

The chosen tunes should be familiar to your ears, and aren’t too melodically complex. As such, they’re a great canvas for applying what you’ve learned here.

Each tune includes a tab and audio example of the basic core melody, to be used as the starting point for creating the arrangement.

See what you come up with, and then compare it with my tab and audio example.

I think you’ll find that, even within the framework of the Round Peak style, the possible ways in which you can deliver any melody are nearly endless!

Do this a few times, and the process will become more and more natural, to the point where you’ll be able to start not only hearing how you might “Round Peak” a melody, but also knowing how to play it on your instrument.