From “Plunky” to “Ringy” and Everything In-Between(y)

Optimizing Your Banjo’s Voice

One of the more unique features of the banjo is the fact that it can be tweaked and modified in so many different ways. One single banjo is capable of a huge range of potential sounds.

And so understanding what your banjo is capable of, and how to bring out those capabilities, can greatly expand the range of possible sounds you can make on your instrument. Furthermore, I often see folks desiring a specific sound thinking they need a new banjo to get it, when the one that already possess can deliver what they’re after with a few adjustments.

Also, it’s quite common for your preferences to evolve over time. The tone you enjoy most when you first start may change as you progress. You may even decide you like different tones for different tunes or different styles of music.

In this module, I’ll be covering what I consider the range of banjo “voices,” and the ways in which you can modify the banjo to optimize them. Some of those modifications involve changing your banjo’s setup, so below I’ve also created some videos covering the basics of banjo setup.

Before we begin, I’ll also add that the more banjo music you listen to, and the greater variety of banjos you hear, the more your ear will start to pick out the distinctions in various tones. In the beginning, a banjo may just sound like a banjo, unless the two instruments are very different (a modern steel strung vs. gourd banjo, for example). Over time, you’ll likely start to hear more of these subtleties (which will in turn likely further shape your own personal preferences).

Sonic Terminology

If you’ve ever been involved in discussions about banjo tone, you may have come away from it with more confusion than clarity.

Sounds are subjective, and so are the terms people use to describe them. One person’s “plunky” may be another person’s “warm,” and so on.

So, when we’re talking about the sonic elements of tone, it’s important that we have a clear understanding of the terminology.

When we strike a banjo string, the vibrations of the string are transferred through the bridge and into the banjo head. The vibrations of the banjo head in turn move the air around it. That vibrating air hits our ears, which we hear as sound. Ultimately, those vibrations fade out, and the sound dissipates.

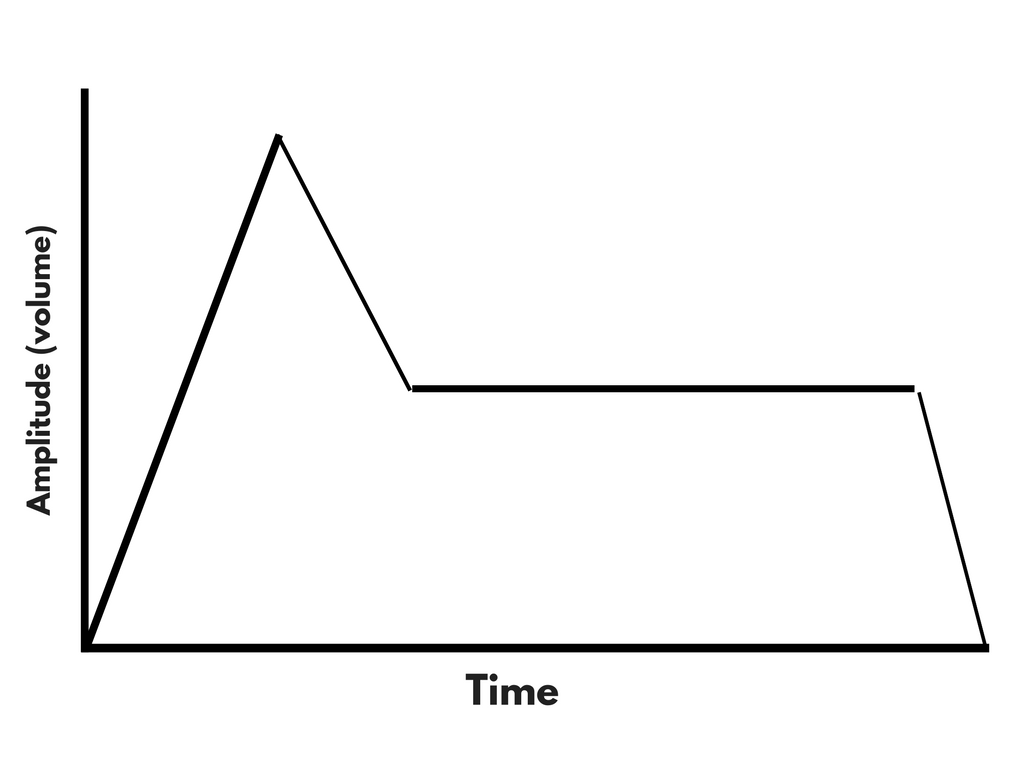

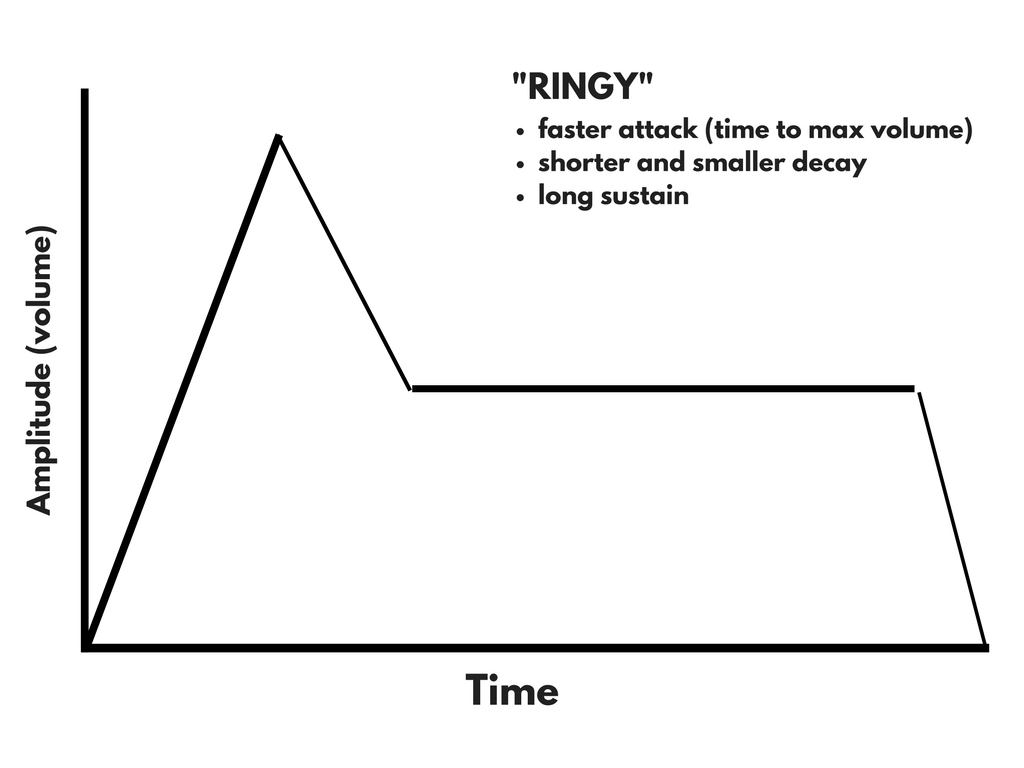

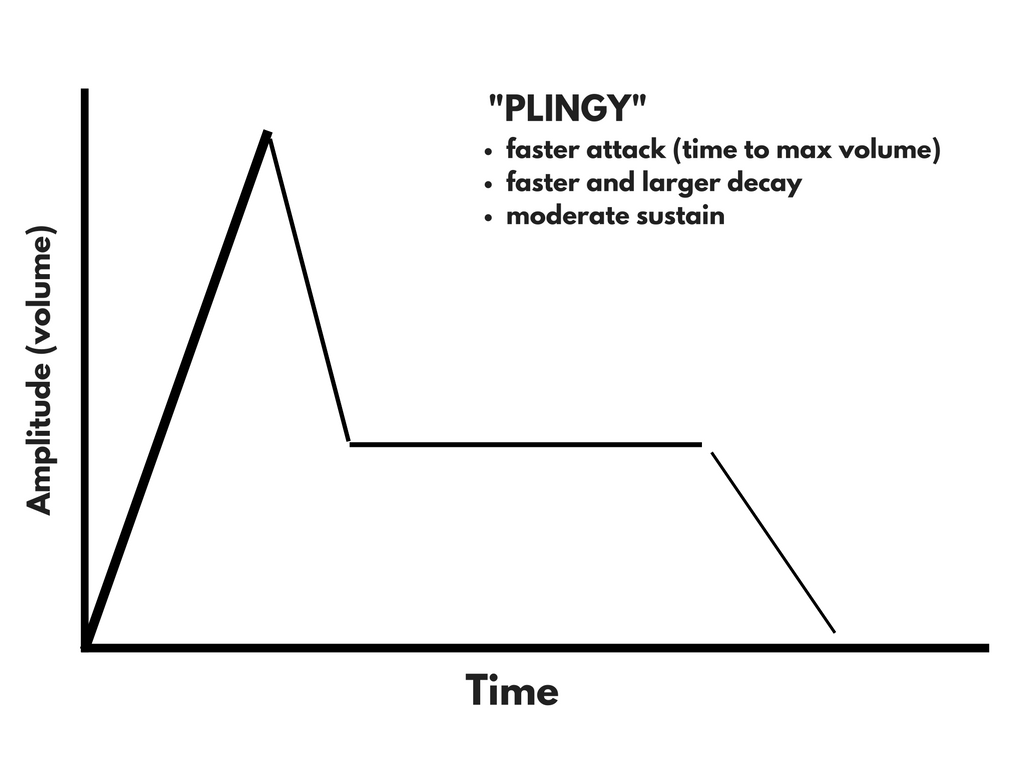

We can represent what happens to the sound after a string is struck graphically as follows (simplified for the sake of discussion):

The various ways in which we can modify a banjo will impact the way in which a string responds to a struck note, thereby changing the shape of this graph, which ultimately translates to differences in the tone of the note we hear.

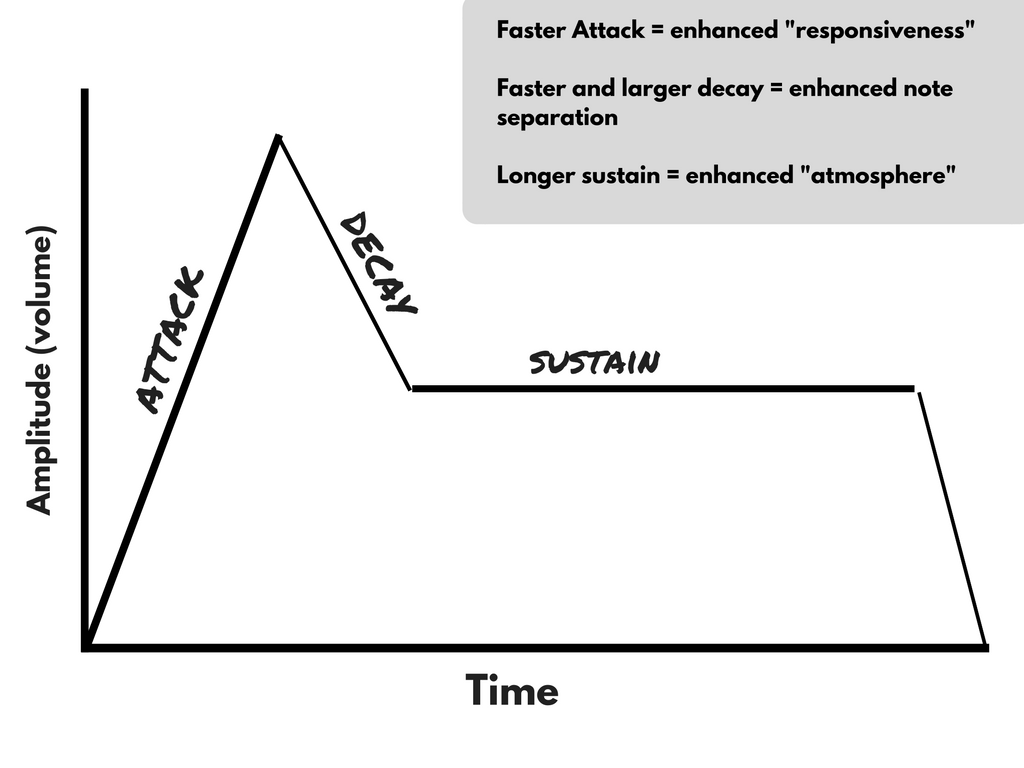

Generally speaking, can divide up the characteristics of tone into a few fundamental elements (note that these terms can be used differently depending on what instruments and sounds are being discussed, which is why we’re defining them here for the purposes of this discussion). When we make adjustments to our banjo, these are the sonic elements we’re changing by doing so.

Those sonic elements are:

Attack: after the string is struck, the volume (also known as amplitude) of the sound rises to a maximum, and then goes down. The time it takes for the sound to reach maximum volume after the string has been struck is the attack.

Decay: most of the time, after the sound reaches maximum volume, it will then reduce in volume to a certain level, then plateau a bit before dying out altogether. The rate at which the sound goes from this initial maximum volume to that plateau is the decay.

Sustain: The overall time in which the sound remains audible after the string has been struck is the sustain.

Timbre: A pure note results when vibrations of air occur at just one frequency (for example, the A above middle C vibrates 440 times per second). But, the vibrations produced by musical instruments do not produce pure notes, but a whole range of vibrations. Some of those vibrations occur at frequencies that are multiples of the fundamental frequency (880, 1320, etc.), and are known as overtones.

The sum total of those vibrations is what contributes to the unique character of each instrument, usually referred to as its “timbre.” Some of those vibrations don’t come directly from the string itself, but from other parts of the instrument set in motions as the string is struck.

The 3 Banjo “Voices”

In reality, the range of possible voices we can get from banjo exist along a continuum, based on the relative contributions of the various elements described above.

But, I think it’s useful here to think in terms of distinct “voices.” One, because it makes talking about these matters easier and clearer. Two, because there are a few types of distinct sounds that have emerged as preferences for most folks, and so categorizing them in this way allows us to understand how we can optimize the setup of the banjo for those specific preferences.

Note that when discussing the fundamental elements that comprise each “voice,” I’m describing them in comparison to each other.

(One of my goals in creating the Brainjo model in partnership with Cedar Mountain Banjo was to create a banjo that would respond well to a range of setups, and whose voice could be customized to suit a player’s tonal preferences. The 3 different “voices” described here are the 3 different types of setups available, since in my experience banjo players tend to prefer one of these 3 sounds (which may change depending on the circumstance and setting)):

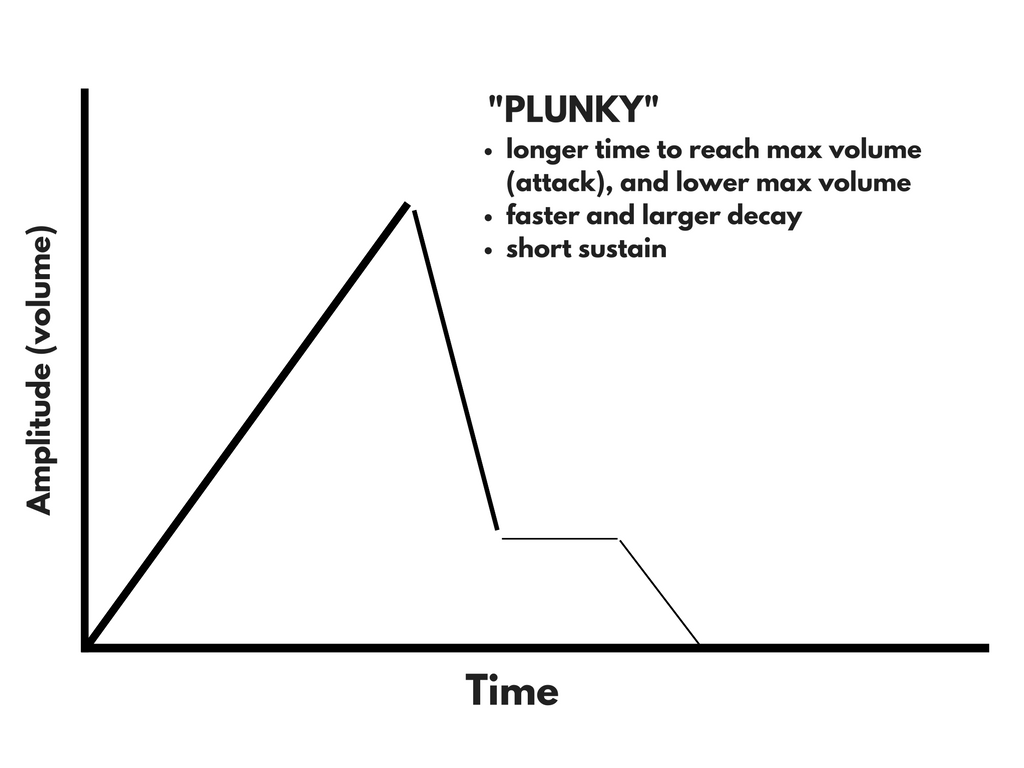

Voice 1: “PLUNKY”

- Sonic elements: shorter sustain, faster decay, slower attack

- Warmer/darker, with more low end frequencies

- Overtone contribution: low

- Factors that enhance “plunkiness”:

- larger rim (i.e. 12-inch diameter rather than 11-inch)

- thinner rims

- looser fit of parts

- gut or nylon strings

- looser head

- thinner bridge

- no tone ring

- “stuffing” in the pot (a sock, rolled up t-shirt, piece of foam, etc.)

- “Strengths” of the “plunky” sound

- Cost. Generally, it’s easier to get a good plunky sound from a less expensive instrument. One of the hallmarks of a banjo from a master builder is that all the parts are well fitted. As a result, the banjo rings as a unit, generally imparting more sustain. And one reason for using higher quality parts overall is because, when the banjo rings as a unit, all of the parts will contribute to the sound to some degree.

- However, with a banjo assembled with lower quality parts, you don’t necessarily want those parts contributing to the sound, so less need to spend the money on ones of higher quality. Additionally, things that can add additional brightness to a banjo (chiefly metal rings) are an additional expense.

- Cost. Generally, it’s easier to get a good plunky sound from a less expensive instrument. One of the hallmarks of a banjo from a master builder is that all the parts are well fitted. As a result, the banjo rings as a unit, generally imparting more sustain. And one reason for using higher quality parts overall is because, when the banjo rings as a unit, all of the parts will contribute to the sound to some degree.

- “Weaknesses” of the “plunky” sound

- Less atmosphere. The tradeoff of having a banjo with less sustain is that there’s less background “atmosphere.” One of the more unique aspects of the banjo tradition are the many “alternate” tunings that folks have used over the years, in part because of the background sound that those tunings give to a tune (the same tune played with the same notes but in different tunings can sound much different because of this). That atmosphere is the result of sympathetic vibrations of all the banjo strings, which are lessened in an instrument with less sustain.

- Less responsive. Another hallmark of a well constructed banjo is how easy it is to play, and one component of this is a banjo’s “responsiveness,” or how readily the banjo reacts to being plucked by the player. A highly responsive banjo is sometimes said to “play itself,” meaning that it responds to a very light touch, meaning less work for the player.

- Generally, a more responsive banjo makes it easier to play more intricate or technically challenging arrangements. On the contrary, a less responsive banjo requires a bit more work, and in some cases may require you to scale back the way you play a tune in response.

- Less volume. Plunkier banjos tend to put out less volume, making them harder to hear in a group setting. As such, there not as well suited for jamming or stringband playing (they can still work for fiddle-banjo duets, especially if the fiddler is good at modulating his or her volume).

- Less “banjo” sounding. For those who associate the sound of a banjo with the sound of bluegrass banjo will find the rounder, thumpier, and more open sound of a plunky banjo quite different.

- What it’s good for: For the reasons mentioned above, a “plunky” sounding banjo is ideally suited for:

- Solo playing, where there are no other instruments to compete with.

- a sparser, more staccato playing style with little use of brushes or full chord shapes.

- Fiddle and banjo duets. A plunky banjo, with it’s short sustain and open sound, can provide a wonderful contrast to the sustaining and sharper sound of the fiddle.

- Old Time music. While many folks associate a sharper, more nasal sound with bluegrass music, a “plunky” sound offers a sharp distinction, one that’s firmly rooted in old-time music, and that showcases different qualities of the banjo.

Voice 2: “RINGY”

- Sonic elements: long sustain, medium decay, faster attack

- Brighter sounding with more high end frequencies represented

- Overtone contribution: high

- Factors that enhance “ringiness”:

- plastic head

- 11-inch diameter rim

- higher head tension (up to a point)

- thicker bridge

- metal tone ring (the tubaphone ring is well suited to this setup).

- heavier banjos (more vibrating mass)

- higher tailpiece setting

- steel strings

- “Strengths” of the “ringy” sound

- More atmosphere. With a ringy banjo, the notes “ring” out longer, and the entire instrument contributes more to the overall sound. Overall, this significantly enhances the background “atmosphere,” highlighting the different characters of alternate tunings.

- Louder. A ringy banjo is generally going to be louder than it’s plunky cousin. This, along with its brighter sound with more high end representation, means it will “cut through” the sounds of other instruments.

- More responsive. A ringy banjo is usually a responsive banjo, meaning that it will respond well to a light touch.

- Sounds like a “banjo.” A banjo with a “ringy” setup will provide the type of tone that many folks associate with the classic “banjo” sound (thanks to the influence of bluegrass banjo).

- Versatility for other styles. While a ringy banjo can be played near where the neck meets the pot (or over a frailing scoop) to produce the more open sound that many old time players prefer, playing close to the bridge produces the sharper sounds associated with bluegrass banjo.

- “Weaknesses” of the “ringy” sound

- Less note separation. The more sustain a given instrument has, the more the notes can blend into each other. So whereas a ringy and responsive banjo may make it easier to play “notier” arrangements, too much ring will mean those notes start merging together.

- Metallic and modern. As mentioned previously, a ringy banjo is more akin to the sound that many associate with bluegrass banjo, which is perhaps the most “modern” banjo sound, which may be less desirable for those wanting a sound that’s more ancient and “old.”

- Highlights lower quality banjo. More overtones in a ringy banjo generally means that more of the banjo components will contribute to the overall sound. If those parts are of lower quality, the resulting sound may not be as pleasing to the ear.

- Muddier in a band setting. While a ringy banjo is good for being heard in a band setting, too much ring can make the result indistinct and “muddy.”

- What it’s good for:

- Playing in multiple styles and genres (including bluegrass).

- Vocal backup, especially more modern, chord based styles.

- Taking over the role of the guitar in certain playing situations (as the “ringy” setup is closest sonically to a guitar).

Voice 3: “PLINGY”

- Sonic elements: fast attack, larger decay, longer sustain

- Brighter than a “plunky” banjo, but with a faster decay than a “ringy” banjo for enhanced note separation.

- Overtone contribution: moderate

- Factors that enhance “plinginess”:

- plastic head

- higher head tension

- 11-inch diameter rim

- no tone ring (or wood)

- steel strings

- stuffing in the pot

- “Strengths” of the “plingy” sound:

- Volume. Capable of cutting through the mix when there are multiple instruments, and stands up well to a fiddle. Generally of similar volume to the “ringy,” but the notes just don’t hang around as long.

- Moderate atmosphere. More than a “plunky” banjo, less than a “ringy” one.

- Responsive. Responds well to a light touch.

- Note separation. Each note is heard clearly, but fades off in time for the next one.

- “Weaknesses” of the “plingy” sound:

- Metallic and modern. For those desiring a deeper

- Less atmosphere. While the faster decay allows for better note separation, it also creates less background atmosphere.

- What it’s good for:

- Notey fiddle tunes.

- Old time jamming.

- Fiddle and banjo duets.

- Vocal accompaniment (especially for traditional songs).

The Impact of Technique

While the components and setup of any given banjo will partly define the resultant sound, banjo players also have the ability to alter that sound in a variety of ways through the use of varying banjo techniques. In this way, it’s possible to coax a variety of “voices” out of the same banjo.

Here are some of the ways in which how you play the banjo can affect the tone of your banjo.

Nail considerations.

- Nail strength. A stronger, stiffer nail will generate a louder note, with a sharper, more focused tone. A softer nail will generate a softer note that may be a bit less distinct.

- Nails vs. pick. Your nail will typically give a “warmer” (more bottom end) note than one generated by a pick (plastic, metal, etc.), as the contribution from the pick will tend to add more high end frequencies.

- Angle of attack. The angle at which your nail strikes the string (perpendicular vs. slightly off axis) will also change the tone of the resultant note. Try experimenting to see what different sounds you can get (but don’t adopt any playing positions that introduce tension in your hand just to accommodate a particular angle of attack).

Playing Location.

- Where you place your hand in relation to the bridge has a significant impact on the resultant sound. Playing close to the bridge will give a sharper, more nasal sound (the tone preferred by bluegrass players), while playing up where the neck meets the pot gives a sound that’s more open and round.